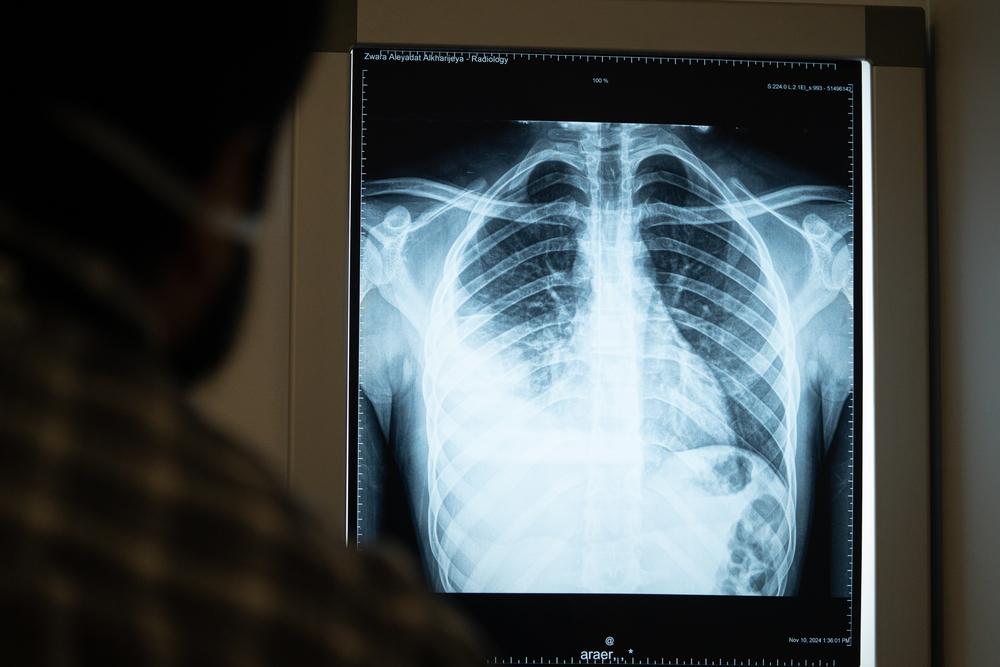

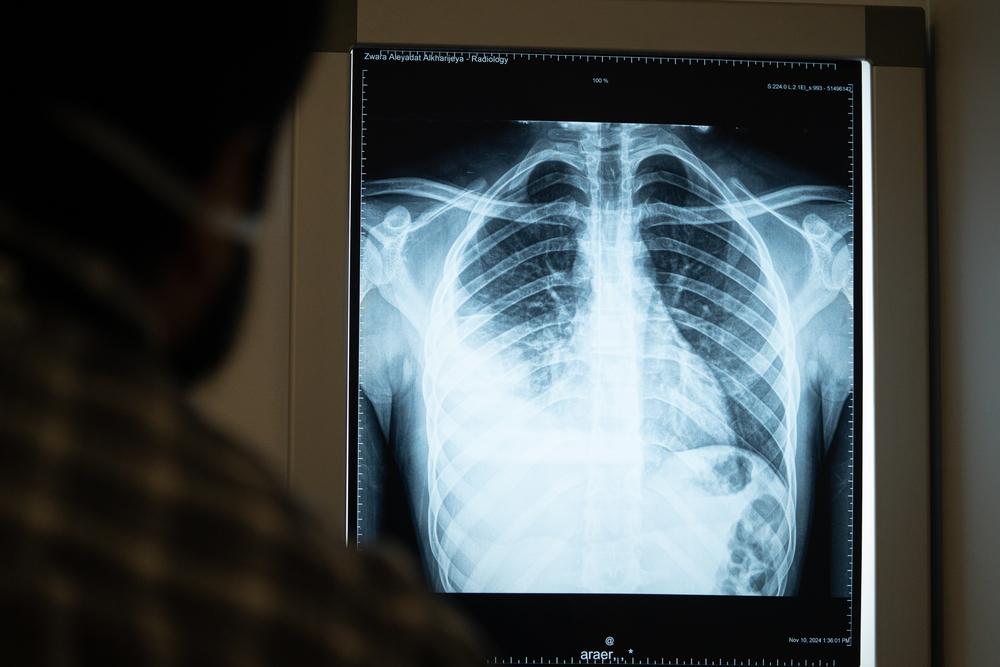

TB is caused by bacteria that spreads by air when infected people cough or sneeze. It most often affects the lungs but can infect other parts of the body, including the bones and nervous system.

The global tuberculosis (TB) crisis is fuelled by several factors, including the alarming rise in drug resistance, reliance on obsolete, harsh drugs that often don’t work, lack of diagnostic tests that are practical for use in low-resource settings, and lacklustre political commitment. Doctors Without Borders (MSF) is one of the main non-governmental providers of TB care worldwide, especially for people with drug-resistant TB, and helps lead global efforts to make newer, more effective treatments affordable and available to those who need them.

We have been involved in TB care for over three decades, often working alongside national health authorities to diagnose and treat patients in contexts ranging from chronic conflict zones and refugee camps to urban slums, prisons, and remote areas. Our programs are designed to provide as many TB services as possible in outpatient community settings rather than in district hospitals. We also work to expand the range of available services by bringing newer, better diagnostic tools and treatments into more widespread use so more patients can access them.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2023 Global Tuberculosis (TB) Report shows that the estimated global incidence of TB in 2022 remains unacceptably high, including for the more difficult-to-treat form of this disease, drug-resistant TB (DR-TB). With an estimated 1.3 million people having died from TB in 2022, and still, only about two out of five people with DR-TB diagnosed and started on treatment; it is critical that countries close the significant testing gap.

Read more

TB is caused by bacteria that spreads by air when infected people cough or sneeze. It most often affects the lungs but can infect other parts of the body, including the bones and nervous system.

Globally, TB crisis has grown dramatically since HIV/AIDS became a widespread epidemic. That’s because people living with HIV/AIDS have weakened immune systems, which increases their risk of contracting and dying from TB—now the leading cause of death among people with HIV. People with other medical conditions that weaken immunity are also at a higher risk of TB infection and death. Children, the elderly, people from regions with high TB rates, and those living in close quarters like prisons, refugee camps, and crowded slums also face greater risk, as do members of households with someone who has active TB.

Many people infected with TB are asymptomatic but can develop an active infection if their immune system becomes weak. Symptoms, which may be mild at first, most often include a prolonged cough and fever. Weakness, chest pain, night sweats, weight loss, and shortness of breath are also common. While lungs are the most common site of infection, TB can affect almost any other body part or organ.

Since TB is airborne it can be easily transmitted in crowded settings, from cramped households and workplaces to health care facilities. For example, people sharing a home with someone who has active TB are at increased risk of developing either a latent (asymptomatic) or an active infection. In these households, sleeping in separate rooms, wearing surgical masks, and using proper cough and respiratory hygiene can limit transmission. Children in these homes, especially those under five years old, are particularly vulnerable. Within health clinics, rapidly attending to patients with TB symptoms and starting treatment quickly for those with active infections lowers the chance they will pass it on to others. Proper ventilation systems within hospitals and the use of face masks that filter out particles in the air can also reduce TB spread.

In recent years the preventive use of TB medications for people at especially high risk of contracting TB—a treatment called Isoniazid Preventive Therapy, or IPT—is gaining ground, although many people who could benefit still do not receive it. It is most often given for defined periods of time (typically 6-36 months) to people living with HIV who do not have active TB, pregnant women in high-TB settings, household contact of TB patients, especially young children, and others with high exposure to TB.

Active Case Finding (ACF) is another preventive approach, based on screening high-risk people (such as household contacts or people with HIV) outside the clinic rather than waiting for them to seek care for their symptoms. ACF can also be used for population-based screening of broader vulnerable groups.

The majority of people infected with TB have not been diagnosed, usually because tests are not available where they live or are not a routine part of primary care. Of the estimated 10 million new cases of TB in 2018, only 7 million cases were reported. Development of simpler, more accurate and cheaper diagnostic tools is, therefore, a critical need.

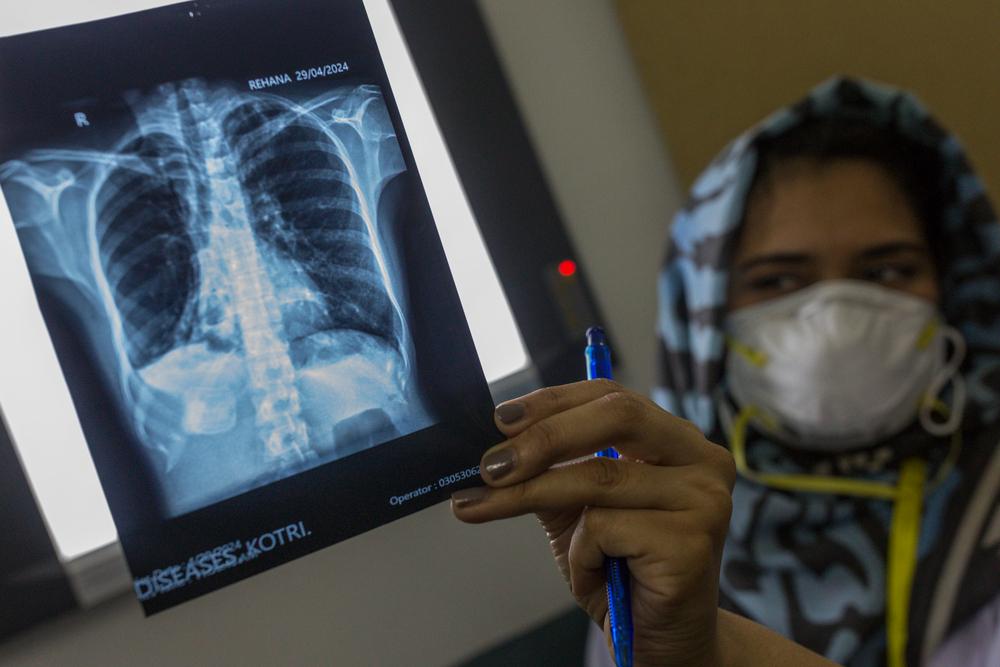

Until very recently, TB was most commonly diagnosed by examining patient sputum samples (phlegm coughed up from lungs) either under a microscope or by bacterial culture. But both methods require a laboratory and trained technical staff, making them ill-suited for many low-resource settings. And neither test is reliable in children, people with HIV, people with TB outside the lungs, or those infected with drug-resistant TB. In the case of culture, it can take as long as 8 weeks to get a result, which delays patients in starting treatment.

In 2010, a much faster, more accurate diagnostic test called GeneXpert MTB/RIF was introduced and is now used for most patients. It gives results within a few hours and can also distinguish between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant TB. While it represents a big improvement, it still requires a laboratory with stable electric power, trained technicians, and other supplies and infrastructure. And since it relies on sputum, it cannot diagnose TB in patients who cannot cough up sputum or who have TB outside the lungs.

In recent years, MSF and others have tested the usefulness of a urine-based test called TB LAM, which is rapid, inexpensive, and easy-to-perform without electricity or instruments. Due to its lower sensitivity (which means that it misses many positive diagnoses) TB LAM cannot replace other tests, but in combination with GenXpert MTB/RIF, it can help diagnose TB cases in people living with HIV and that would have otherwise gone undetected.

Practecal trial announcement

Uncomplicated, drug-sensitive TB is curable, but treatment takes at least six months and relies on a cocktail of the same harsh antibiotics that have been used for decades.

A growing number of people infected with multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) are not cured by the two most powerful first-line antibiotics. As a result, most patients face between nine months and two years of treatment. Over this period they must swallow over 10,000 pills and endure 6-8 months of painful daily drug injections, often along with severe side effects that range from nausea and joint pain to psychosis and partial or total hearing loss. This should begin to improve, though, since new research has found a shorter regimen with these drugs that is no less effective even for MDR-TB. Patients with TB resistant even to the second-line drugs used for MDR-TB are said to have extremely drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), which is even harder to cure.

In the last few years, much better outcomes have become possible using new, more effective, less harsh medicines. These improved treatments rely on three new drugs--the first new TB medicines in 50 years. For two of them (bedaquiline and delamanid) the best combinations with other TB drugs are still being evaluated, while the third drug, pretomanid, was developed as part of a ready-to-use regimen for treating XDR-TB.

Yet there are still big treatment challenges to solve. Access to the new drugs is extremely limited: fewer than 5 percent of patients who could benefit are receiving them, and they are not available in many countries most affected by TB. Also, most TB drugs are not made in formulations adapted for children, and effective treatment for TB/HIV patients is particularly challenging.

Alongside operational research to improve how we deliver care, we have several clinical studies in progress to develop the best combinations of new and old drugs for drug-resistant TB, aimed at finding shorter, all-oral regimens. We also conduct policy research in high-burden countries to identify barriers that hinder the use of new tools and approaches recommended by the WHO. This research helps drive our advocacy on reducing the costs of new tools and scaling up broad global access to improved treatment strategies, diagnostics, and models of care.

For most TB patients treatment is long and difficult, often involving harsh drugs, and debilitating side effects—especially for those with MDR-TB, who may also face long periods of hospitalisation. These factors make it difficult for many people with TB to seek or stick with treatment. In response, and working within each country’s national guidelines, MSF has introduced strategies to simplify treatment, make it more tolerable, and bring it closer to patients.

A key aspect of expanding access to TB care and helping patients complete their treatment is decentralisation—treating patients in community-based clinics and no longer requiring hospitalisation for those with MDR-TB, a shift ushered in by changes to WHO recommendations in 2014. Since then, many countries have made this change, although some still lag behind. To help implement this shift, MSF supports many local health clinics in diagnosing, treating, and monitoring TB patients.

An important part of decentralising care is task-shifting. For settings with too few physicians, this means training clinic nurses to give patients TB medications and monitoring their response over time. It also means training ‘expert patients’ to support, educate and counsel their fellow patients. Task-shifting allows us to care for many more people and to foster stronger links with local clinics, which makes it easier for people to continue their treatment.

Another strategy MSF uses to decentralise care is to offer home-based options for patients receiving treatment for MDR-TB. These build on Directly-Observed Therapy (DOT), where patients visit the clinic daily so a healthcare professional can watch them take their daily dose of medication—a widely-used approach to help patients with drug-sensitive TB adhere to complex regimens, and to help caretakers monitor their response. As an alternative to DOT, MSF now offers video-observed treatment to some MDR-TB patients who have difficulty reaching our clinics.

As challenging as it is to manage TB in adults, it is even harder in children, whose less robust immune systems make them especially vulnerable to developing TB. Diagnosis can be complicated since children often cannot cough up phlegm. And many drugs that treat TB—especially MDR-TB—are not produced in paediatrics doses, leaving children to take bitter-tasting pills cut into small pieces and crushed. Prolonged hospital stays can isolate children from their families, peers, and schooling. What’s more, children are often excluded from clinical trials that test shorter regimens and new medications, so the benefits of improved, more tolerable treatments take longer to reach them.

For these reasons, our TB programs work to improve TB care for children. One way is through partnerships with Ministries of Health, like that which established our paediatrics TB program in Tajikistan. This program, which focuses on drug-resistant TB, uses specialised diagnostic methods such as using a nebuliser machine to help children produce sputum, and introduced treatments with new DR-TB medicines like bedaquiline and delamanid, and without injectable drugs. For children who cannot swallow tablets, the MSF pharmacist prepares medications in a syrup suspension, improving palatability of these medications and allowing for more exact dosages. The program employs teachers to provide basic schooling, runs a therapeutic playgroup, and holds group counselling sessions for hospitalised children to help them cope with the challenges of living with TB.

A fundamental step to effectively combat the TB epidemic is that affected countries adopt the WHO's recommended best practices for TB diagnosis and care. Our Step Up for TB 2020 study—a collaboration between the MSF Access Campaign and the Stop TB Partnership—shows that too few high-burden countries have updated their national policies to reflect new WHO guidelines, leaving thousands of people more vulnerable to this curable disease. 'Step Up for TB’ is part of a series of reports since 2014 that have helped countries identify barriers to adopting the newest WHO guidelines and measure progress over time, and have helped inform efforts of TB advocates.

Through the Access Campaign we also work to expand access to better TB drugs and less harsh, more tolerable drug regimens, by advocating for a wide range of reforms and for drug companies to lower the price of crucial new medications like bedaquiline.

TB is the leading cause of death among people infected with HIV, whose weakened immune systems increasing their risk of TB and worsen its course. Ensuring that people with HIV are taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) as well as TB preventive therapy increases their protection against TB. For people with both HIV and TB, integrating treatment for both infections at a single clinic—a relatively recent development in many settings—makes it far easier and more likely they will receive the care they need. At MSF our integrated, decentralised model of care typically brings together diagnosis, treatment, and patient support and counselling for patients with both HIV and TB.

A new initiative aims to improve TB testing and treatment of children, who are particularly vulnerable to the potentially fatal disease. Watch the video to find out more.

Watch nowThe most widely used test for diagnosing active TB in low- and middle-income countries relies on examining a patient’s phlegm under a microscope. This method, developed nearly 140 years ago, detects less than half of all TB cases and largely fails to detect the disease in children and people co-infected with HIV – who usually can’t produce the sputum needed – and those with drug-resistant forms of TB. A diagnostic test, Xpert MTB/RIF, was introduced, and we use it in many of our projects, but it can't be used in many resource-limited settings.

A course of treatment for uncomplicated TB takes a minimum of six months. Drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) treatment requires taking a cocktail of drugs and can take up to two years or more, but trials are ongoing to treat it in six to nine months. It is vital that a patient completes their entire course of treatment, even when they start to feel better; incomplete treatment can lead to drug resistance developing. Decentralising treatment by having people cared for at home can help them adhere to treatment and overcome any obstacles they may face.

When patients are resistant to the two most powerful first-line antibiotics (rifampicin and isoniazid), they are considered to have multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Treatment is long and arduous, with the drugs having many potential side-effects, including psychosis and deafness. People can take as many as 20 pills a day for two years - only to have a cure rate of little better than half. Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) occurs when a patient is resistant to second-line drugs. Only a third of people with XDR-TB are cured.

Most drugs to treat TB are old and toxic. But in the last decade, bedaquiline, delamanid and pretomanid, three new TB drugs - the first in half a century - were developed, giving patients hope and treatment providers options. But making these drugs available to patients who desperately need them has been painfully slow. We estimated that, in 2016, only around one in eight people with DR-TB who could have benefited from the lifesaving newer drugs bedaquiline and delamanid were treated with them.

Most of the drugs used to treat TB are decades old, while some were not originally developed for TB use, and/or have toxic side effects. Treatment itself for DR-TB can take up to two years. For these reasons, research into new, shorter, more effective drug regimens is urgently needed. We are participating in two clinical trials, EndTB and PRACTECAL, to find new treatment regimens. The EndTB trial enrolled its final patients in October 2021. In the same month, the PRACTECAL trial announced in preliminary results that its six-month, all-oral regimen cured nine out of 10 patients.

By donating to MSF, you form part of, and enable, a network of individuals worldwide which can continue our lifesaving work with tuberculosis.

Donate now