Migrant children and pregnant women are being denied potentially lifesaving care in South Africa

To highlight just how devastating this can be for people affected, we’re relating two patient stories that were shared with our teams at the Tshwane Migrant Project, and brought to life through illustration by artist Balekane Legoabe.

Sanctioned to death

Three-year-old Miriam*, whose family are from Uganda, has cerebral palsy and associated epilepsy. She requires specialist paediatric care as well as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and medication that is often only available in a hospital setting.

Miriam’s mother was assaulted during pregnancy while living in Mozambique as a refugee, and this injured the foetus significantly. Miriam’s father tried to get help from international and national human rights’ organisations, upsetting the Mozambique authorities. The family fled to South Africa after receiving death threats.

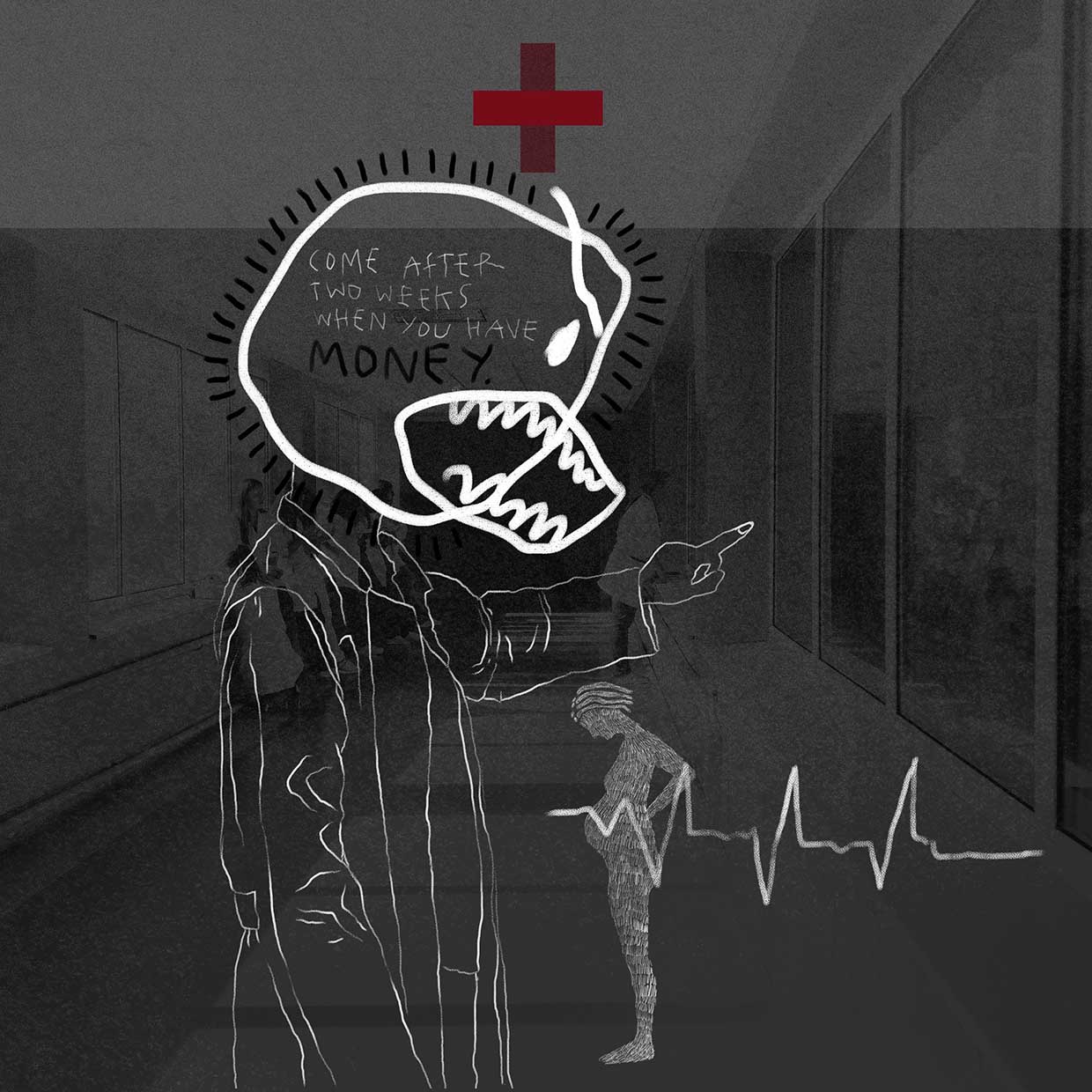

When Miriam’s parents sought specialised medical care for her in Tshwane, the hospital administration demanded payment before opening her file, insisting that exemption criteria only apply to South African patients. This violates South Africa’s National Health Act stating that healthcare is free for all children under six.

Miriam’s family doesn’t have any income, and they struggle in accessing healthcare and medication for her. Because she cannot get regular access to medical support, her condition is poorly managed, and she is constantly ill.

*Names changed to maintain anonymity

Waiting & Praying

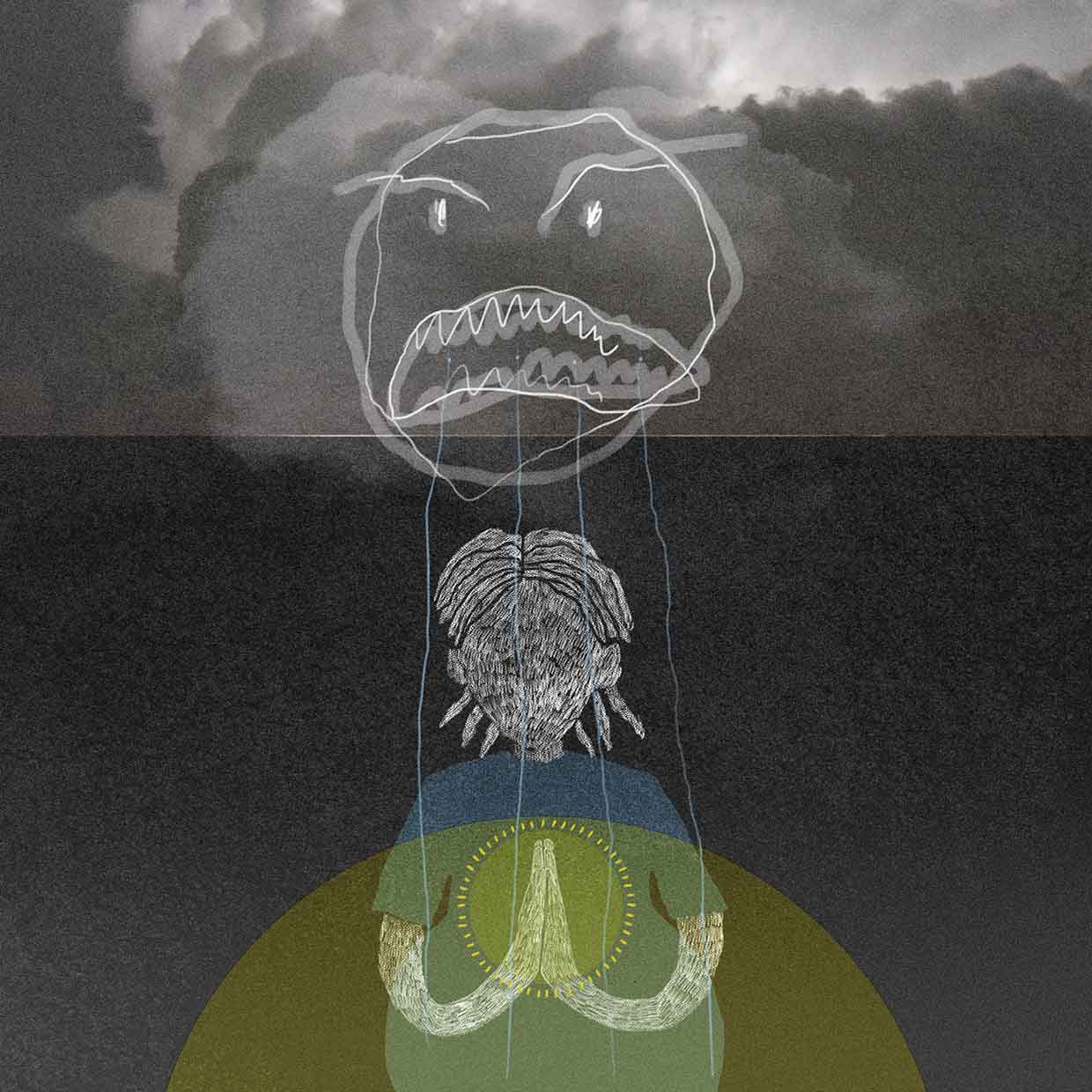

Safi*, a pregnant migrant woman from the Democratic Republic of Congo, visited a clinic in Tshwane and was considered a high-risk patient due to her elevated blood pressure and history of miscarriage. She was referred to a nearby tertiary hospital and was seen by the doctor, who asked her to return in two weeks with a payment of about R500. She and her husband are unemployed and being unable to afford the payment, Safi did not return for her appointment.

In Gauteng, MSF has witnessed a dangerous trend whereby the department of health levies fees against migrants for child and maternal health services, even when they are unable to pay.

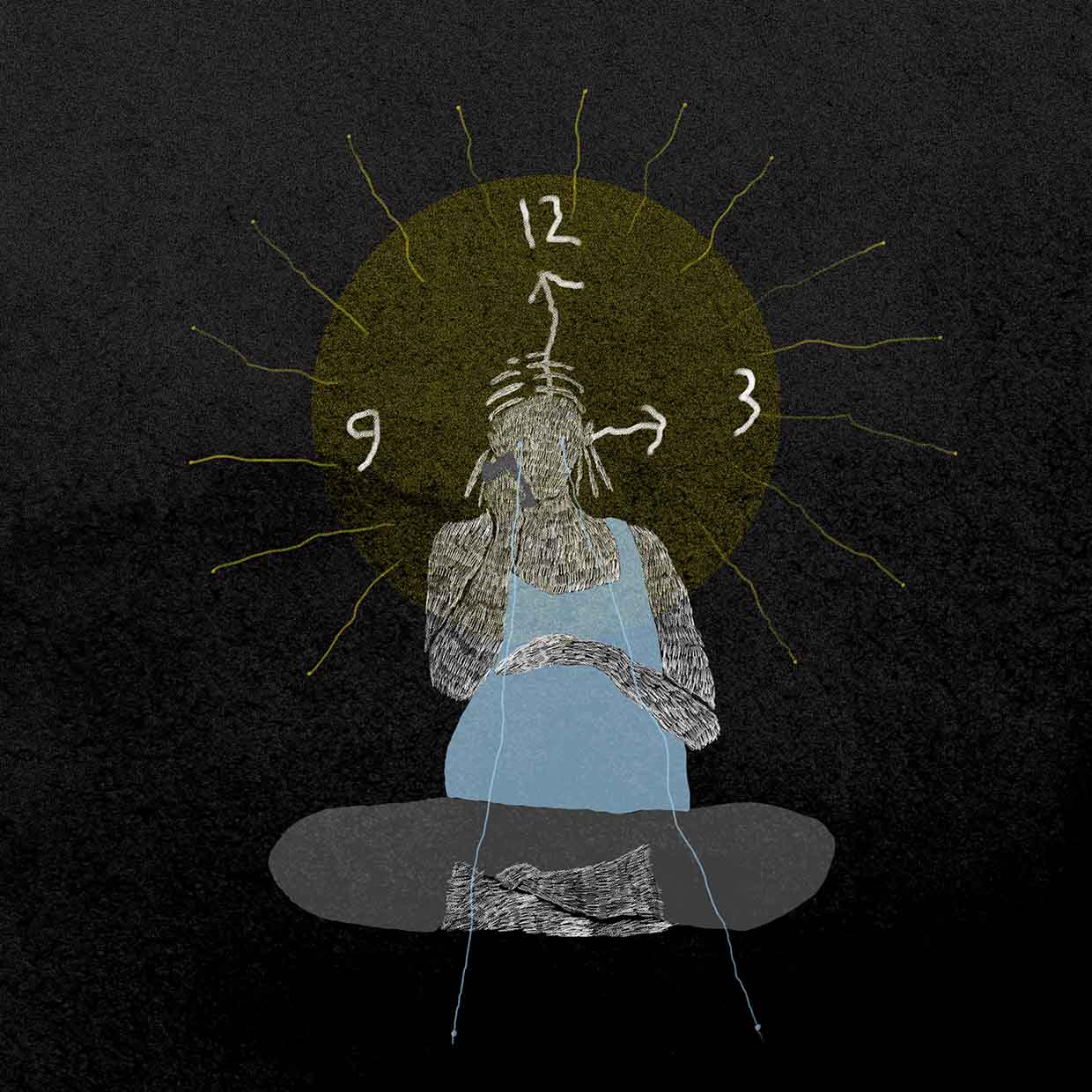

By her 38th week of pregnancy, Safi had dangerously high blood pressure. Left untreated, this could have resulted in seizures and other severe complications and cost the lives of both Safi and her baby. With the help of MSF, she was taken to the hospital as an emergency patient for a caesarean section. She delivered a healthy baby and was discharged after a week. While she received signed proof of birth from the hospital administration and wasn’t asked to make any payment on discharge, she has now received a hefty bill of R37,000. With no means to pay this bill, Safi is afraid to seek further medical care for herself or her child. This is her story.

*Names changed to maintain anonymity