A person lives to serve their children.Ghassan Fakhri Jabar

Ghassan Fakhri Jabar carefully puts the coffee cup down. There’s an atmosphere of pent-up excitement in the small apartment where we talk in Agios Panteleimonas, a vibrant and multicultural part of Athens, the Greek capital. Ghassan has been living here for four months now, after undertaking a long journey without access to diabetes treatment from Palestine to escape conflict.

Children and grandchildren are running around the apartment, and daughters, wives and daughters-in-law from the extended family are preparing food in the tiny kitchen, laughing and chattering together while trying to keep the children in some kind of order so the father can tell their story. Around the rooms of the apartment, suitcases and bags are piled up, packed and ready to go.

On Friday, Ghassan will set off on the last leg of his journey from Gaza to Germany, where two of his sons and their families eagerly await the reunion with their father and the rest of the family.

It's a familiar story of flight, exile and the dream of family reunion. But the journey Ghassan has just taken was made far more dangerous by the fact that he lives with type 2 diabetes and needs to control his blood sugar levels with a strict routine of tablets and insulin.

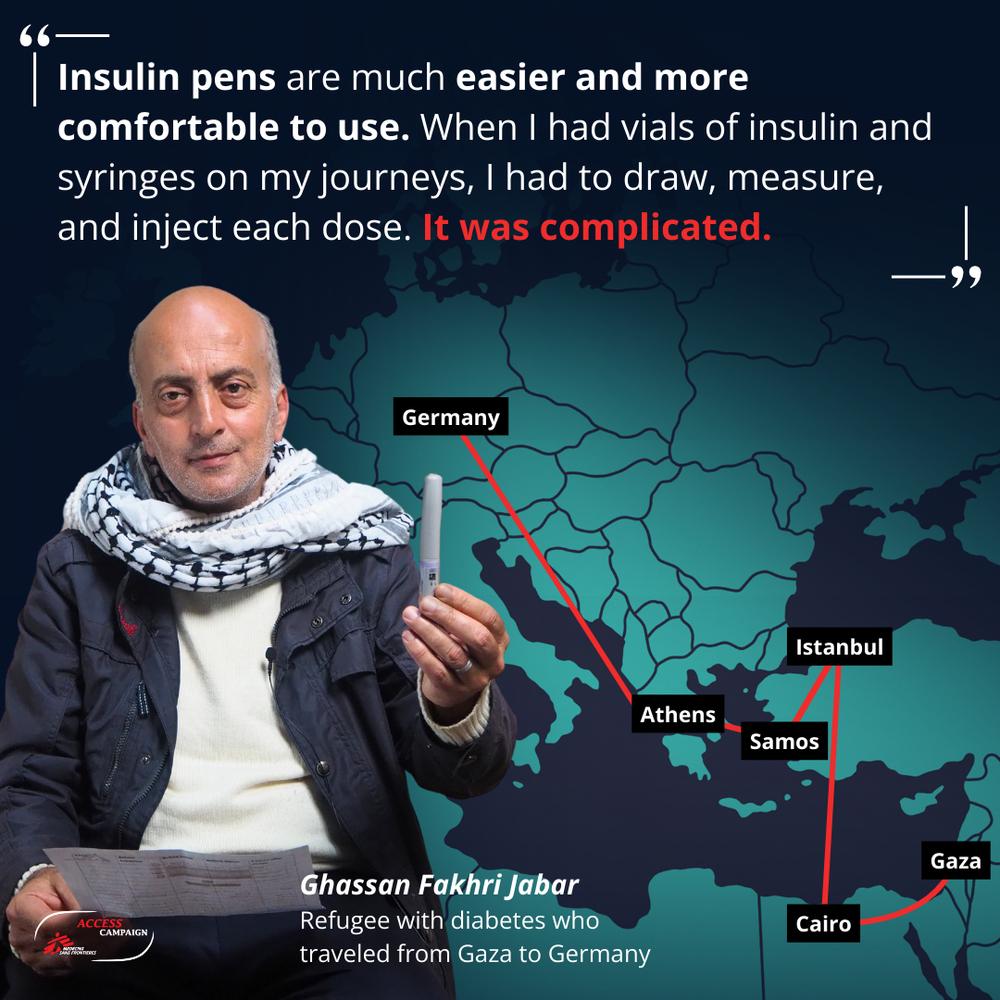

Without regular monitoring of his blood sugar levels and insulin injections, Ghassan risks falling very ill or worse. In a journey of over eight months from Gaza, through Turkey, to the Greek island of Samos, and finally to Athens, Ghassan has been through some desperate and challenging moments on account of his medical needs as a person living with diabetes. We asked him to share his story.

“I was a simple man, a government employee in Gaza. My two sons left for Germany, and four years later, I decided we should all leave Gaza and go there to support them. I’d been diagnosed with diabetes around 15 years earlier, and was receiving insulin in vials regularly from UNWRA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency) for free. My life was in order, and my illness was controlled. When I told UNWRA that I was planning to leave Gaza and travel to Germany, they gave me a two-month supply of insulin in vials with syringes to take with me.

There were thirteen of us travelling together. I sold my car and put my financial affairs in order, and we left Gaza through the Rafah crossing. We then took a bus to Cairo airport and flew to Sabiha (Istanbul) airport in Turkey.

We planned to travel to Greece together when we got to Turkey, but I didn’t have enough money. So, I sent my youngest children and my married children ahead of us on to Greece. My wife, daughter and I remained behind. We didn’t know it would take us eight months and 15 failed attempts before we would complete the journey to Greece.

Back in Palestine, I was taking my diabetes medication consistently and keeping my blood sugar levels regular. That stopped when I got to Turkey. When the insulin in vials given to me by UNWRA ran out, I tried to buy some more, but it was too expensive.

When the insulin was unavailable, I tried to adjust to my circumstances, I reduced my food intake and exercised and walked around in order to try to keep my blood sugar levels down. I deprived myself of many foods, drank a lot of water and tried to eat healthy things like tomatoes and cucumbers. But I didn’t have enough money to buy much to eat.

During this time, we tried to cross over to Greece, paying smugglers. Fourteen times, we set out by boat, and each time, the Turkish Coast Guard caught us. They took all our bags of belongings, clothes, food, and my medications and threw them into the sea before sending us back to Turkey.

Ghassan and his family finally made a successful crossing to the island of Samos on their 15th attempt.

I was sent to prison for three or four days each time we were caught. They gave us a piece of bread with cheese the size of my palm, and we ate the same meal for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for several days. This food wasn’t healthy for someone in my condition, so I tried not to eat it in order not to raise my blood sugar levels. Sometimes, my blood sugar would fall to 60 (a dangerously low level), and then I would fall into a coma. They would take me to the hospital and give me treatment to raise my sugar level.

They didn’t want me to die in prison. Then, they sent me back to prison. Sometimes, though, the hospital refused to treat me because, with a blood sugar level of 700, they considered me dead already, and they sent me on to another hospital. They told me to manage independently when they stopped detaining me and took me back to the camp where we stayed.

Ghassan and his family finally made a successful crossing to the island of Samos on their 15th attempt.

Upon arrival in Samos, the police escorted us, and we were taken to get a medical check-up. I told them I was diabetic, and they tested my blood sugar, which was 600 (a dangerously high level). They called an ambulance and transferred me to the hospital immediately. I spent the night there before returning to the camp on the island, where I started taking insulin daily at 10 AM in the mornings.

When we left Samos two and a half months later and came to Athens, I was directed to the MSF clinic.

They checked me and found my blood sugar was high. The chronic disease doctor gave me insulin pens and monitored my condition every 15 days. I recorded my blood sugar levels in the morning, afternoon, evening and after dinner.

The insulin pens are much easier and more comfortable to use. When I had vials of insulin and syringes on my journeys, I had to draw, measure, and inject each dose. It wasn't very easy. Access to any insulin was the main thing, but it would have been so much easier for me with convenient pens, and the injection is light and painless. I appeal to the whole world to support MSF in continuing to provide insulin through pens, not vials.

The MSF doctor was strict with me, emphasising the importance of caring for my health. He cared a lot about me and was kind. I am very grateful for what he did.

Thank God I adhered to the programme he set for me and took the insulin regularly. My blood sugar readings in the fourth month were excellent. I was lucky to be able to store my insulin in the fridges of the local supermarket. People locally have really helped me.

Now I’m ready to move on. And this time I am prepared.

Dr Fanis gave me two months’ worth of insulin pens. My advice to people with diabetes is that if you have to travel, make sure you stay in touch with a doctor, take insulin without interruption and avoid stress and anger.

I’m ready now. You must challenge the disease, or it will defeat you. I challenged the whole world to reach my children. I faced death for their sake. Thankfully, my life is well-organised and healthy due to God’s grace and the doctor’s help. I feel successful. My children are eagerly awaiting us. They feel we did our utmost for them and were in their service. Thank God.”

After the interview, Ghassan stretched his legs and introduced us to his friends in the locality. Soon, this time in Athens will be just a faded memory, but there’s still time to share a final coffee and enjoy the company of friends, so many of whom have shared experiences of traumatic journeys, fleeing unstable and conflict-ridden homes, and now facing uncertain futures. In an ever-changing and unpredictable world for Ghassan and so many others like him, the value of family and friendship is the only constant.