Over one billion people suffer from neglected tropical diseases (NTDs); however, despite this vast figure, NTDs continue to be overlooked. This World NTD Day, we’re taking stock of the progress that has been made to prevent, control, and eradicate NTDs, as well as highlighting the huge challenges that remain.

World NTD Day was designed to put a spotlight on them and to remind the governments of affected countries, pharmaceutical companies, philanthropists and the governments of wealthy nations – all of whom have the power to support – that there is much more to do.

The diseases are distressing, disfiguring and stigmatizing, most affected individuals live in the most remote and underserved regions of the world's poorest countries. Many are excruciatingly painful, and they are often deadly. However, they can be treated – and they can also be prevented.

Below is a whistlestop tour of the current state of play: five notable achievements, and five of the biggest obstacles that remain and continue to block progress in the fight against NTDs.

- Noma added to the list of NTDs in 2023

In 2023, Noma was finally added to the official list of NTDs, bringing much-needed visibility and hope for investment in research, prevention, and treatment. The campaign for this recognition was led by Nigeria, with support from MSF and others.

Noma is a deadly, highly stigmatized disease that begins as mouth ulcers, quickly turning gangrenous and destroying facial tissue. Survivors suffer from severe disfigurement and disabilities, often hidden away due to stigma. If left untreated, it is fatal for 90% of children. With limited research, the exact causes of noma remain unknown. Current estimates, over 25 years old, suggest 140,000 new cases occur annually, with 770,000 people living with its lasting effects.

For over a decade, MSF has worked with the Nigerian Ministry of Health, running a noma hospital in Sokoto that provides treatment, reconstructive surgery, mental health support, and community outreach. Due to Noma’s stigma and the difficulty in reaching affected communities, the true scale of the disease remains unknown. Its addition to the NTD list is a critical step in addressing this devastating illness, potentially leading to increased resources and global action to combat its spread and impact.

2. END Fund steps in after the UK’s abrupt funding cuts

In 2021, the UK’s abrupt overseas aid cuts ended its crucial support for life-saving visceral leishmaniasis treatment in East Africa. As one of the largest historical funders of NTDs, particularly visceral leishmaniasis, its withdrawal left a major gap in the fight against these diseases. The parasite is transmitted by sandflies that progressively attacks and destroys tissue that is vital for immune function, and without treatment can rapidly become fatal. Initial mild symptoms develop into a prolonged fever, enlarged spleen, anaemia and substantial weight loss. The cure is a combination of two drugs injected daily for 17 days.

Through intensive advocacy by MSF and others, a new funder – the END Fund – was found. However, access to prompt diagnosis and treatment remains huge challenges for many visceral leishmaniasis patients around the world – especially in East Africa. Recent global political shifts, as well as many competing emergencies, are threatening funding more than ever – sustainable longer-term support is required to ensure that we make progress to prevent and cure and eventually eliminate visceral leishmaniasis, and other NTDs.

3. MSF will soon join the fight against female genital schistosomiasis

MSF is working to better identify and address schistosomiasis in humanitarian settings, in South Sudan in other affected countries. Jonglei State, South Sudan, where MSF currently runs a hospital in Old Fanfak, has the highest documented burden of schistosomiasis. Schistosomiasis is caused by a waterborne parasite found in freshwater lakes and rivers.

MSF suspects many girls and women suffer from female genital schistosomiasis (FGS), an advanced form of the disease, which causes severe inflammation and reproductive and urinary complications and can even lead to fatal cancers. While it is one of the “big five” NTDs receiving limited funding, existing interventions focus mainly on prevention, which leaves women and girls already suffering from advanced diseases without treatment. As an overlooked form of an already neglected disease, MSF is committed to ensuring women and girls receive accurate diagnoses and the best possible care.

4. GAVI expands rabies vaccine access

In 2024, GAVI launched an ambitious programme to improve vital access for patients to the rabies vaccine after animal bites. This means that ministries of health will finally be able to stock the vaccine in clinics and hospitals and be able to quickly vaccinate any people bitten by dogs at no cost to patients.

In wealthy countries with easy access to vaccines, dogs are among those vaccinated to keep the disease under control. While this move from Gavi will not include any vaccinations for dogs, countries can include rabies on the list of vaccines they request from GAVI for humans who are bitten. Except for dengue fever and chikungunya, rabies is the only vaccine-preventable NTD. However, in many of the 150 countries where it is still a huge threat to human life, stocks are extremely limited, and the cost of the vaccine is high.

Rabies spreads to humans through bites from infected mammals, usually dogs. It is preventable with prompt post-bite medical care, if the post-exposure vaccination is not received in time, the patient becomes infected with the virus. Once symptoms appear, the disease is 100% fatal, as no cure exists.

5. Guinea is the latest to eliminate sleeping sickness

In the past 25 years, sleeping sickness cases have dropped by 97%, leading to its elimination as a public health issue in countries like Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Benin, Togo, Uganda, Chad in 2024, and now Guinea. This success highlights the impact of political will, funding, and investment from pharmaceutical companies in developing safer, more effective treatments for NTDs. Despite these achievements, 1.5 million people remain at risk.

Sleeping sickness is caused by parasites transmitted from tsetse fly bites, and in one form of the disease, it can move to the acute stage – when the parasites attack the brain and spinal cord – within just a matter of weeks. This causes sleep disruption, convulsions, confusion and eventually a coma. Without treatment, it is fatal.

For decades, the only treatment was an arsenic-based drug that killed one in 20 patients. In the 1970s, a new drug dramatically improved survival rates. In the 1990s, the manufacturer, Sanofi-Aventis, planned to discontinue production, threatening to undo progress. Fortunately, pressure from the WHO and MSF persuaded Sanofi-Aventis to prioritise sleeping sickness, donate the drug and develop new, better, more patient-friendly treatments in collaboration with DNDi - the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative. This collaboration and continued investment have led to further advancements in medicine. Now, a simple and safe oral treatment is available.

6. New conflicts threatening progress in the fight against NTDs

When war erupts, neglected tropical diseases become even more neglected. Fragile health systems collapse, surveillance is disrupted, and previously controlled diseases can resurge. Vigilance is crucial.

In North Darfur, Sudan, we are on high alert for a potential outbreak of visceral leishmaniasis. Though no cases have been confirmed in our emergency response projects yet, other parts of Sudan are known hotspots. Displacement and malnutrition create ideal conditions for outbreaks, so we are preparing our teams.

Mass displacement brings two major risks: people with no prior immunity moving into endemic areas face high infection risks, while those already infected who flee to non-endemic regions may spread the disease. This is our concern in North Darfur, where healthcare services have collapsed.

Access constraints remain severe, with vital medical supplies stuck in transit for months. Diagnosis is also difficult, requiring skilled staff and functioning labs—both in short supply. Since North Darfur has not historically been a hotspot, health teams are less familiar with the disease.

To prepare, we have sent rapid tests and drugs and trained teams to support the Ministry of Health in responding quickly if an outbreak occurs.

7. Major financing gaps persist

NTDs struggle with severe funding shortages, but the “big five” receive most of what little is available. These diseases attract donors because they can be tackled quickly through mass drug distribution.

For the remaining 16 NTDs, control methods are often more complex and costly, leading to even greater funding gaps. The WHO estimates a $2 billion shortfall for NTD control from 2023-2025, not including medicine costs.

Major donors like France, the UK, the EU, and BRICS could make a real difference. Instead, they are scaling back support rather than maintaining or increasing funding for these diseases of poverty.

8. Antivenoms in short supply, exorbitantly priced

Snakebites are the deadliest NTD, yet antivenoms remain scarce, overpriced, and often substandard.

Antivenoms are region-specific, produced in small batches, and often weaker than needed, requiring multiple vials. With little market regulation, each country must verify the effectiveness of local snake venoms. However, weak health systems make proper assessments nearly impossible, leaving many without reliable treatment. Most snakebite victims live far from health facilities that may not even have antivenom in stock. Even if they reach a clinic, the high cost makes treatment unaffordable.

The good news is that in 2017, the WHO launched an assessment of existing products – requesting samples from various manufacturers – and the results are being disclosed in real-time. With this audit, we hope it will put pressure on the producers to improve their products. In addition, we hope it will trigger more domestic and international financing to acquire more doses of quality antivenoms and distribute them free of charge to snakebite victims in need.

9. Diagnostic tests are in short supply

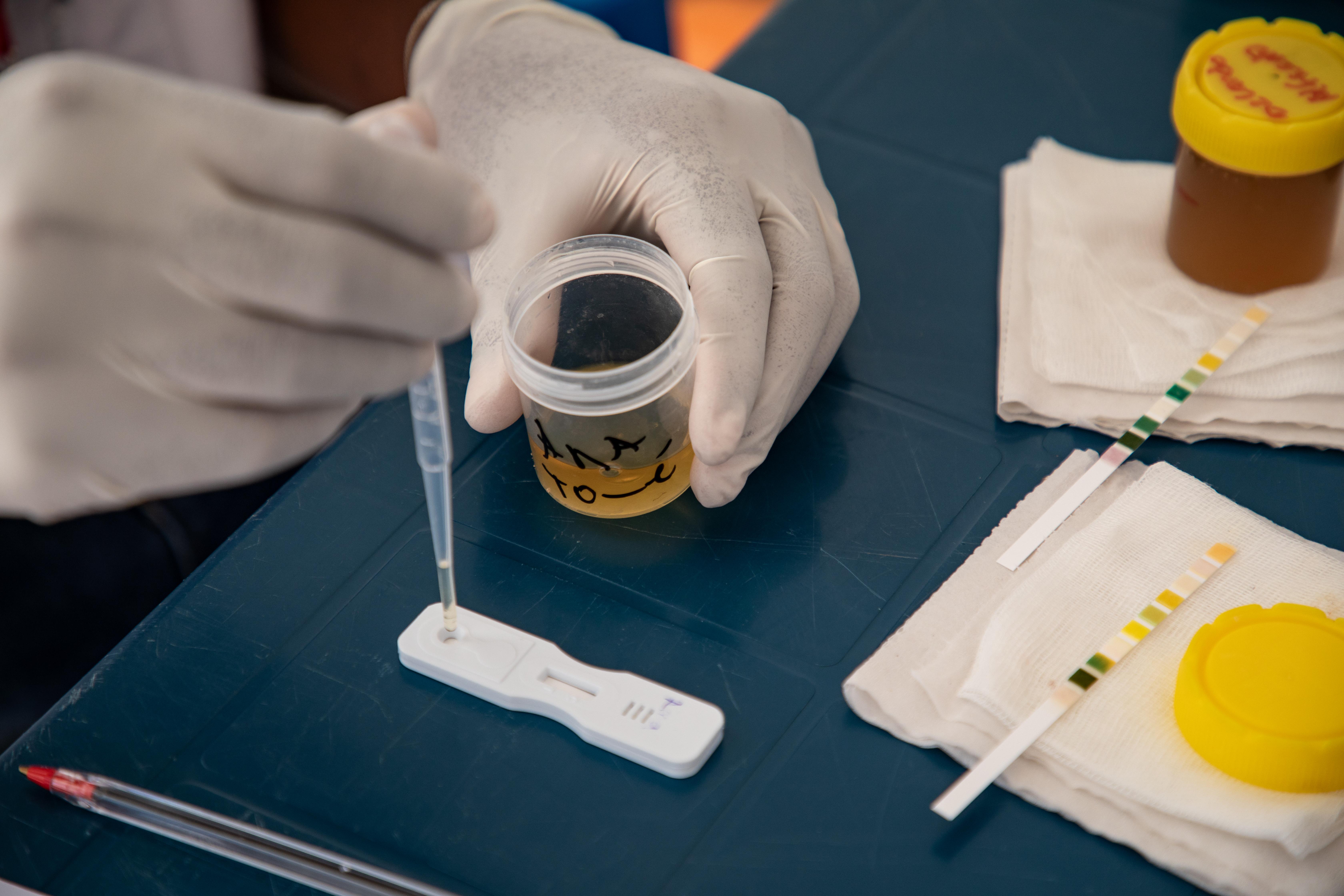

Continued surveillance of NTDs is vital for keeping them under control – and for this, diagnostics are key. Many diagnostic tests are not always accurate, so investment is needed to improve them. Although some new diagnostics are being developed, they are for very niche markets, so it is difficult to persuade large companies to invest in them. There is far less financial backing for diagnostic tests for NTDs. Many NTD medicines are produced by large drug companies like GSK who may wish to donate the drugs in exchange for a good reputation. The companies producing diagnostic tests are much smaller by comparison, and this is not an option for them. There is no global access mechanism for diagnostic tests for NTDs, so countries have to individually purchase their own.

It is vital that diagnostics are also brought closer to communities – the ability to effectively diagnose these diseases early and to initiate prompt treatment is essential for patients’ well-being and to prevent the spread of disease. This requires reliable, affordable, easy-to-use "point of care" rapid tests.

10. Reduced funding for research

In the last few years, after relative stability, funding for research and development for NTDs notably declined. If this continues as a downward trend, the final steps of major medical breakthroughs will be put at risk. Research is extremely time and resource consuming: many early innovations never “make the grade” in terms of efficacy and safety, and so have to be abandoned. Late-stage trials are expensive, and if there is no funding for them, new compounds to treat NTDs will have no chance of coming to market to save lives.

Visceral leishmaniasis, dengue and Chagas disease, for example, have new compounds that are ready for clinical trials, and a vaccine for schistosomiasis is also in the early stages of development. Snakebites are another NTD where clinical trials could soon start. In 2019, the Wellcome Trust invested in a seven-year research and development project for snakebites, but this funding is expected to come to an end in 2026. Although there are some exciting new products in the pipeline – with a universal antidote being the desire of most within the research community – in order for this to be achieved, funding needs to be prioritised and sustained in the longer term, and the future of all of this progress is now hanging in the balance.