Today, infections caused by resistant microorganisms cause around 700,000 deaths per year, which is mostly attributed to low-income countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) fears that resistant microorganisms will be the leading cause of death by 2050.

Without proper diagnostics and staff who can interpret test results in middle-income and low-income countries, antibiotics are prescribed blindly – driving the rise of resistant bacteria worldwide.

"To stay healthy, we need a diversity of good bacteria because they create a kind of balance against the bad ones," says Dr. Nada Malou, a microbiology expert at Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and the inventor of Antibiogo, a free diagnostic aid app designed to combat antibiotic resistance.

The Role of Accessible Diagnostics in Low and Middle-Income Countries

Antibiotic resistance is part of the broader concept of antimicrobial resistance, which means that bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites mutate and no longer respond to available drugs.

Most infections with symptoms such as fever and sore throat are caused by viruses, which is why antibiotics are ineffective. If it is a bacterial infection, you need to know which bacteria it is to prescribe the right antibiotics.

"Non-specific treatment with antibiotics not only kills the bad bacteria, but also the good ones. If the drugs are used too often and incorrectly, the number of good bacteria decreases, and there's a risk that the bad ones will take up more space."

A free diagnostic aid application to counter antibiotic resistance created by Dr Nada who worked in Yemen for MSF

"If a patient seeks medical care for a sore throat or fever here in France or Sweden, the doctor can determine whether it is a virus or a bacterium with a rapid diagnostic test," says Nada Malou.

The diagnostic tools produced are often expensive and developed based on the conditions in high-income countries, excluding low-income countries and middle-income countries.

"Health facilities in low-income countries and middle-income countries are often not equipped with this kind of diagnostic capability, or the laboratory services needed to support them. At best, it is available in the larger hospitals."

"If I was a doctor seeing a child with a high fever and the choice was between giving antibiotics blindly and doing nothing at all, I would prescribe them as well. We know that there is a window of around 24 to 36 hours to act when a very sick child comes in."

"Many countries we work in cannot afford to purchase the tools on a large scale. Several of the machines can't be kept in temperatures of over 30 degrees and are sensitive to, for example, dust and humidity, which is a major challenge in the conditions we work in," says Nada Malou.

Diagnosis is a neglected area in medical science, especially in low-income countries and middle-income countries. Nada Malou explains that the problem consists of two parts: the lack of access to functioning diagnostics and laboratories as well as the lack of microbiological expertise.

Bridging the Microbiologist Gap Using Antibiogo

Having experienced this gap firsthand, Nada Malou had an epiphany. It was 2016, and she was working for MSF in Aden, on the southern tip of Yemen.

"There is a huge gap here. For example, it is estimated that 400 years of training would be needed in sub-Saharan Africa to cover the shortage of microbiologists."

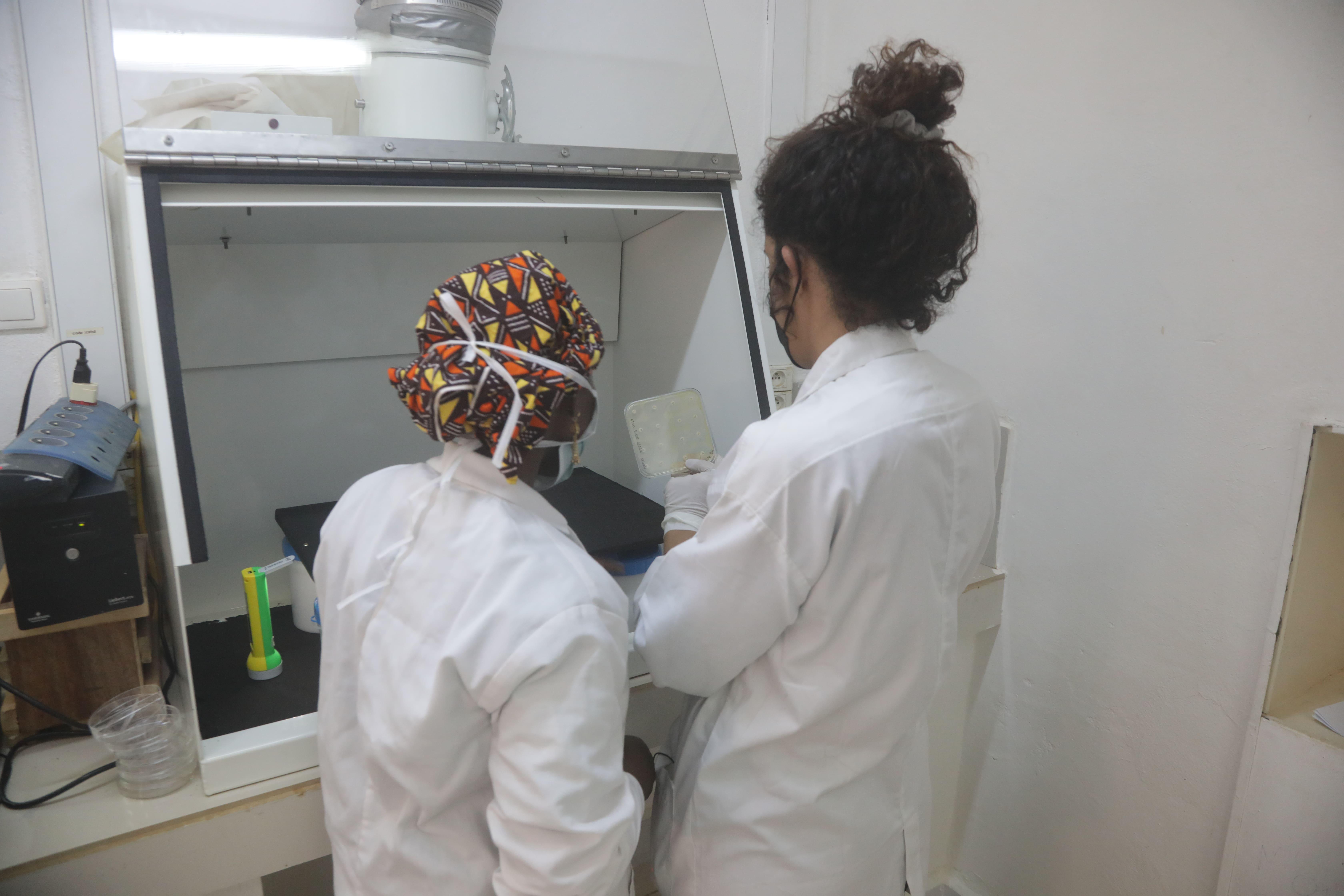

"I was in charge of setting up a laboratory in MSF's hospital, where we were receiving war-wounded patients, many of them with wounds infected by resistant bacteria. But we couldn't find a microbiologist."

"You need to be a microbiologist for that, which requires several years of specialised training. So, staff in the hospital would process the tests, but every day, we had to send the results for validation remotely, which was not sustainable."

Nada Malou began to fantasise about inventing something that could help non-specialist staff interpret test results before prescribing antibiotics.

"I envisioned a phone application where you take a picture of the test result, and the app then guides the prescription. As soon as I got back from Yemen, I contacted the MSF Foundation headquarters in Paris."

"We got a big grant and a group of engineers who helped us develop the AI features of the app," says Nada Malou.

Back in Paris, Nada Malou presented her idea, called Antibiogo, to the MSF Foundation. They were interested, and the next few years were spent developing the idea into a finished project proposal. In 2019, Antibiogo won the Google AI Impact Challenge, which opened new possibilities for the project.

In 2022, Antibiogo was implemented in MSF projects with access to microbiology testing in Mali, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Jordan.

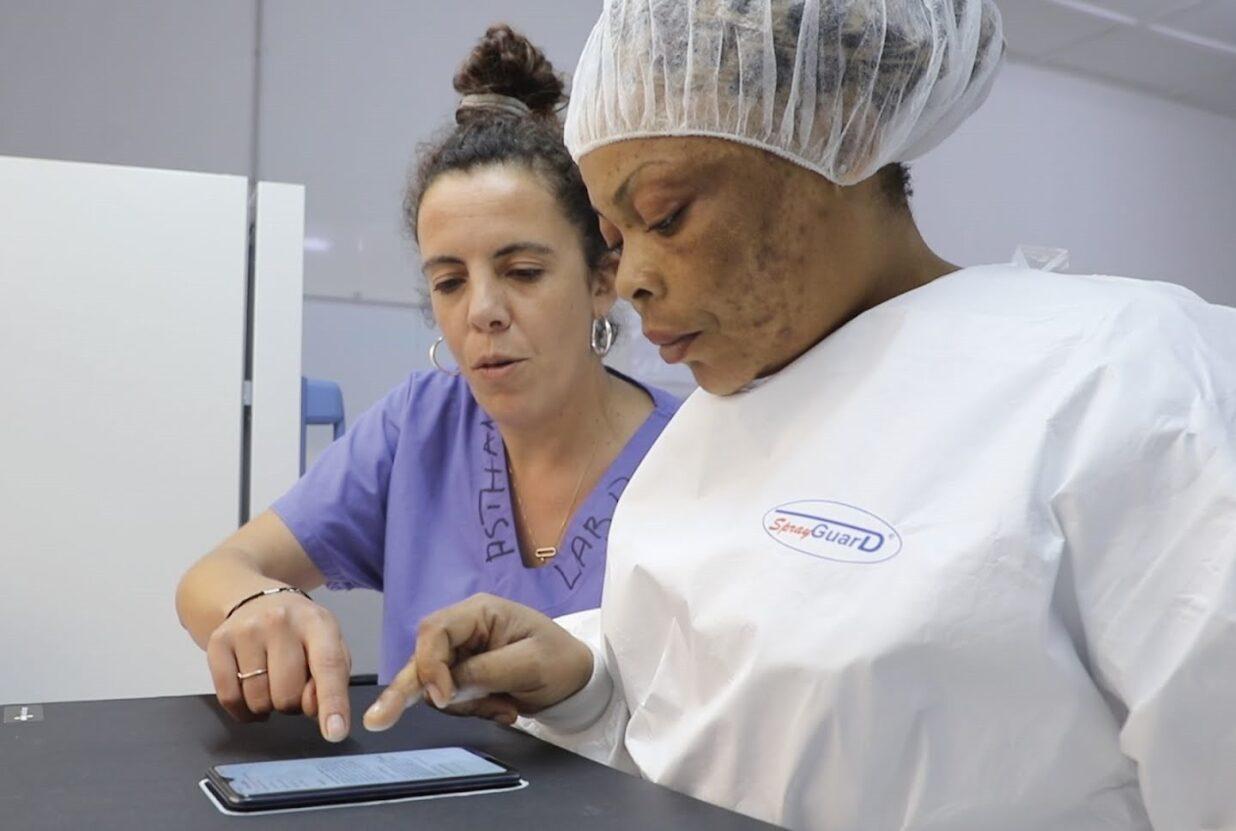

"The app acts as a sounding board and asks you questions to help you learn more. It also interprets the results and provides comments for the technician, either for more tests or confirmation of a diagnosis."Dr Nada Malou

"The app acts as a sounding board and asks you questions to help you learn more. It also interprets the results and provides comments for the technician, either for more tests or confirmation of a diagnosis. Then it sends messages to the clinicians to help with the patient's treatment," says Nada Malou.

Antibiogo is now CE-labeled, which is a stamp issued by the EU that a product meets environmental, health and safety requirements, and in recent months it has also begun to be rolled out in public health care facilities as well, such as Mali. Other countries are planned for 2024.

"Our goal is for the app to serve as a diagnostic test and a broad-based learning tool in countries where there is a significant shortage of microbiologists. But this must go hand-in-hand with increased access to functioning diagnostics and laboratories in these countries. This is why we are continuing our advocacy efforts towards medical companies and politicians."

Hopes for Future Advancements

Nada Malou hopes that the attention Antibiogo receives will help shed light on the problems surrounding diagnostics and will contribute to more medical products being developed with low-income and middle-income countries in mind.

"That's why I hope that more people in MSF will have the courage to take their ideas forward – no matter how crazy they may seem. We are on the ground and see the reality in many places where few other organisations are working, so our ideas for new medical solutions are needed," says Nada Malou.