Share This

Videos and Photos19 October 2018

18-year-old Mohammad Muslim came to Bangladesh from Rakhine in early September. “We had to come because the Myanmar government was torturing us,” he says. “They were looking for young men and boys. They tied them up and threw them in the river. They drowned. The beautiful women, they raped. Those who were not beautiful or who were old, they would kill with a knife. I saw this with my own eyes.” Witnessing these traumatic events has had a profound effect on Mohammad: “I’m not feeling well inside my body ... I used to eat well, sleep well before, but not now. My head, chest, even my nails start shivering ... I keep thinking of those things. Whenever I think of my country I am not peaceful... my nerves start hurting in my neck.” He continues: “I feel sick whenever I think of my country and that makes me sad.”

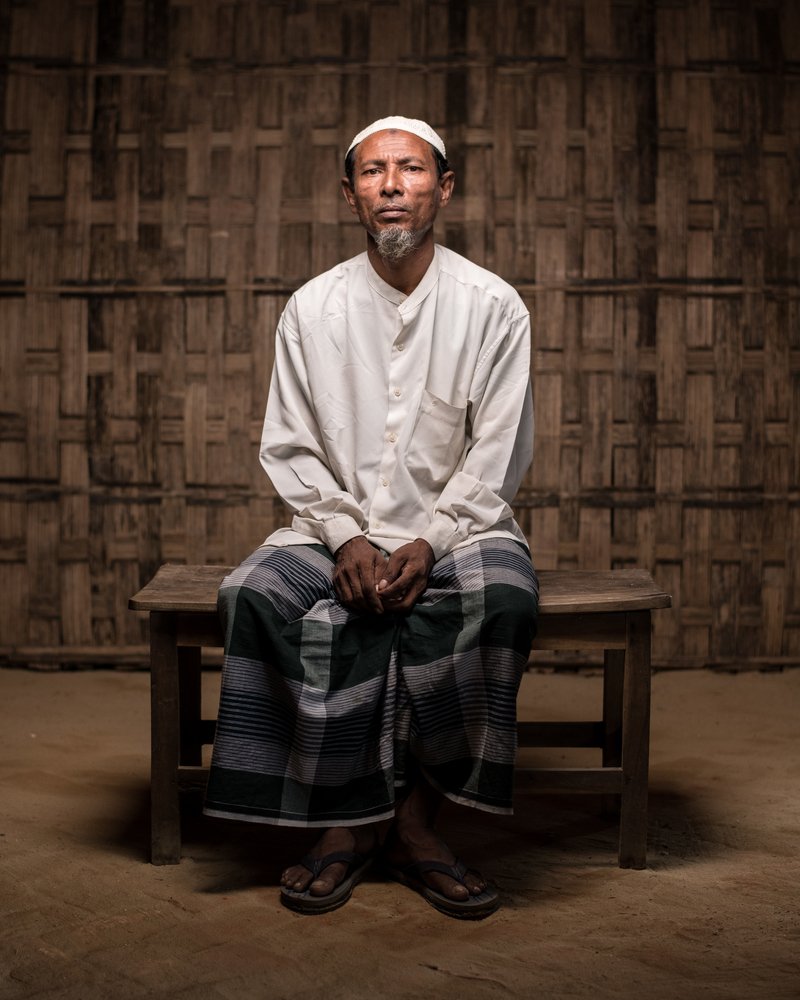

50-year-old Rohingya Mohammad Yunus sold cooking fuel for a living in Myanmar before he fled to Bangladesh in September 2017.

55-year-old Basha Miah was a fisherman before he fled Myanmar in September 2017.

39-year-old Nur Muhammad Azad (known as Azad) is an MSF mental health, who has worked with Rohingya refugees for over seven years. For many refugees, life in the camp has exacerbated the trauma of the violence they experienced in Rakhine. "When they arrived here in Bangladesh, many Bangladeshis helped them in various ways with food, education, clothing and economic support. But now this help is reducing and they have no way to earn money. Everyday this problem is making them more depressed.” Azad went on to say that the symptoms of their mental health conditions often manifest physically, which makes it hard to diagnose and treat. “Here most of the people think that the physical problem is the biggest problem and they need a doctor to treat it, but they don’t understand that what they have is a mental problem.”

Mabia Khatun, 40 years old, fled from Myanmar to Bangladesh in November 2017. “I was feeling unhappy in Myanmar because Myanmar’s police were cutting our heads off, imprisoning our children and killing us. ”The violence directly affected her family: “In the morning I heard the news that my brother and sister had been killed. I went to see. Everywhere in the house there was blood.”They had been decapitated. Now in Cox’s Bazar, “I feel happy in the camp because I can sleep at night without any problems - in Myanmar we slept during the day and not at night, because the police would take our neighbors and family members at night. I will never forget what happened in Myanmar. Sometimes it comes back to me. I feel unhappy when I think about it. I can’t sleep and I have body pains. I get dizzy when I think about it.” Mabia’s children have likewise been affected: “I have small children. When my mother tells the children that we will one day return to Burma [Myanmar], the children say ‘no, if we go back, the military will kill us.’ They are afraid to go back."

25-year-old Latifa Begum, with her two-year-old baby Nurujan, came to Bangladesh from Myanmar 11 years ago. Over the last 12 months, she has been receiving treatment from the MSF mental health team. “I’ve had problems in my head since I had the baby,” she says. “I had dizziness and loss of appetite… When someone talks around me it makes me unhappy.”

70-year-old Noor Alom was a rice farmer in Myanmar before he fled to Bangladesh on 30 August 2017. He describes the attack on his village: “People were being burned; they were burning them in their houses. The people in my village started running, so I ran too.” All six members of his family escaped physical harm, but the attack, coupled with the loss of all his worldly possessions, source of income, and new identity as a refugee, has taken a psychological toll. “My head started hurting after I arrived here,” he says, describing what doctors commonly diagnose as physical manifestations of mental illness. “I was happy with my family (in Myanmar). Now that I cannot support them or move freely, nothing makes us happy. If we were home we could celebrate (the Muslim festival of) Eid. But we can’t do that here, we just sit and wait.”

22-year-old Setera Begum came to Bangladesh from Myanmar on 19 September. She came to Bangladesh, she says, because people were being killed. “In my area they were being decapitated. I could not tolerate what was happening in front of my eyes.” Like many in her village her house was burnt down. Her son was in the house when it caught fire. She managed to save him but he was badly burnt on the buttocks. But it is the people who were killed that occupy her mind: “I do not feel peaceful when I think about the people being decapitated and I will not feel peaceful again until those people accept us as Rohingya.” Since arriving in the refugee camp, she’s had to cope with further tragedy: “I was pregnant. I was taken to Cox’s Bazar to deliver the baby. The baby was born dead. I was not feeling well as my son was born dead … I am not feeling well in my body. I am not at peace.” She’s been taking medication since. “I feel good taking the medicine,” she says.

24-year-old Enayet Ullah sits with his 45-year-old mother Habiba Khatun. In August 2017 they fled violence in Rakhine and crossed into Bangladesh. “We came to this country because the Burmese people were killing our relatives and burning our houses,” says Enayet. They escaped without Enayet’s father, who was arrested by Burmese authorities. Enayet describes his state of mind since leaving Myanmar: “I think about my land and I miss where I used to live... when I start thinking about everything that happened I begin feeling weak inside and get out of control, my brain does not work anymore.” Habiba expands on the mental health issues Enayet faces: “Sometimes he speaks nonsense and hits people... he breaks things. He used to take medicine in Myanmar; when we came here we didn’t have any medicine. Two or three months ago he started crying about his father then started talking nonsense.” The pair sought help from MSF: “After taking some medication he is alright,” says Habiba.

32-year-old MSF Psychologist Supervisor Shariful Islam has seen a Rohingya refugee mental health crisis unfold before him over the last 12 months. He says the mental health challenges have not disappeared over the past year, but changed: “At the beginning of this crisis, we mostly noticed the patients who come to our department, or to other areas of our health facility. We provide a huge amount of psychological first aid for patients and we noticed that some of the stable patients became destabilized after this crisis, especially the psychotic patients. And now we are noticing that depression, anxiety, hopelessness and domestic violence, especially intimate partner violence, has increased. We are receiving more and more of these kinds of patients now. In our sessions we notice that now the Rohingya patients who come to the mental health department say: ‘I have no hope and all I can think about is how they tortured me, how they killed my mother, how they killed my baby.’ They tell us that when they remember all of this, they are unable to control themselves, behave erratically, and sometimes beat their family members. We are noticing that these kind of patients are significantly increasing.”

26-year-old Mohammad Yunis, shown here with his six-year-old son Osman, arrived in Bangladesh at the end of 2017. “We came here because the Mogh people (derogatory term for local Rakhine Buddhists) were shooting and burning people. My uncle and two cousins were shot and killed in front of me.” He also describes how he saw his parents being beaten up. The trauma of the violence, coupled with finding himself a refugee, has taken a toll. Mohammad Yunis states: “I’m not feeling well here. My brain has become out of control.” He also describes the physical manifestation of his mental illness: “I used to be fat. I’m getting thinner and thinner day by day thinking about what happened.” He went to MSF for help: “I could not sleep because I used to roam around, not sleeping and hitting people. So I started taking medicines and they help me.” Comparing life in the camp with life in Myanmar, he says: “Living in a camp - I don’t want to - it’s not a good environment. We had good land, a good house. I’d be very happy if I could go back there. But the Burmese people burnt my land and house.” Ayesha and her children are out of immediate danger now, but the events of that day often return to her. “I cannot forget what happened. Every moment I think about it and it causes me pain inside.” When asked what she does to make herself feel better, she just replies: “What can I do to feel better?”

26-year-old Mohammad Yunis, shown here with his six-year-old son Osman, arrived in Bangladesh at the end of 2017. “We came here because the Mogh people (derogatory term for local Rakhine Buddhists) were shooting and burning people. My uncle and two cousins were shot and killed in front of me.” He also describes how he saw his parents being beaten up. The trauma of the violence, coupled with finding himself a refugee, has taken a toll. Mohammad Yunis states: “I’m not feeling well here. My brain has become out of control.” He also describes the physical manifestation of his mental illness: “I used to be fat. I’m getting thinner and thinner day by day thinking about what happened.” He went to MSF for help: “I could not sleep because I used to roam around, not sleeping and hitting people. So I started taking medicines and they help me.” Comparing life in the camp with life in Myanmar, he says: “Living in a camp - I don’t want to - it’s not a good environment. We had good land, a good house. I’d be very happy if I could go back there. But the Burmese people burnt my land and house.”

22-year-old Rohingya refugee Tayeba Khatun says she came to Bangladesh one day before the Muslim festival of Eid in 2017. She describes the attack that caused her to flee: “It was early in the morning when the military arrived. They announced on a loudspeaker that we shouldn’t leave the house. I told the men not to leave the house. The military went house to house and eventually, they arrived at ours. They took away my father-in-law and brother-in-law.” Then they came for the women. “When I was being dragged out my husband tried to save me and was shot dead. Then they dragged me away,” says Tayeba. “There were five military men. Three stood outside to manage the situation, two raped me… they raped me until I lost consciousness. When I came to, I collected my children and escaped. I am telling you all of this so that we can get justice.” The attack happened a year ago but it’s never far from Tayeba’s mind. “Whenever I’m alone I think of all of this. Whenever people discuss the fact that my husband is dead I think of it all over again… I do not feel peaceful. I cry often. When I do, I gather my children around me and cry a lot.” When asked what she does to try and feel better she says: “I feel better with my children. When women come to my house to gossip and we talk I forget those things.” She turns again to her husband: “If my husband was alive my children would have had a better future, the food they want, the clothes they want. I can’t provide them with the things they deserve.”

It took 19-year-old Majeda 14 days to reach Bangladesh after fleeing Myanmar in early September 2017. Like many Rohingya women, she endured sexual violence. She describes the attack: “The Mogh (derogatory term for Rakhine Buddhists) tortured [raped] me and I became pregnant. After torturing [raping], they would kill the girls. They would take the girls to the forest and do this. If you went into the forest today you would find their bones.” Arriving in Cox’s Bazar, she learnt she could abort the foetus. Her mother helped her. “My mother learnt that we could drop [abort] the baby. I went to hospital and they gave me some medicines and it went away.” Discussing the attacks, she reflects: “The thinking never stops. Whenever I think about it, the blood rushes to my brain and all the nerves in my body hurt."

60-year-old Rohingya refugee Dilbahar came to Bangladesh one day after Eid 2017. “They were shooting from the other side ay us. I saw the neighbourhood on fire. I saw my son get shot in the neck and die. I had to bury him there. I lost my daughters and husband. I lost my other son. I don’t know if they are alive or not. The Mogh (derogatory term for local Rakhine Buddhists) chopped off the heads of my sister and her daughter, I saw their bodies.” Dilbahar’s husband survived the attack but was left disabled after being beaten by the military. She talks about life in the camp: “Though it is not peaceful we try to find peace here. Because we lost our country, because we were being hit and injured and because we have no country to call our own. But we try to find peace here.” The memory of the violence haunts her. “I can’t bare the pain inside when I think of the things that happened.” She has turned to God for comfort. “Whenever I feel that pain, I pray and ask for help. Whenever I pray and ask for help from the Almighty, I feel peace. I try to convince my heart that although my sons are not here, they are dead, I pray that we will be able to return there peacefully.”

12-year-old Rohingya refugee Johura Begum lost 14 of her 16 family members when the Burmese military attacked her village in Rakhine state, Myanmar. The only other survivor was her 10-year-old brother. “The military people told us that we would be fine, that we shouldn’t worry. They separated the men from the women … I saw everything with my eyes. People were gathered by the side of the river. The pretty women were taken somewhere. The older men, they were killed. Before they were killed they were given the task of digging holes in which to bury themselves.” Johura managed to get away. “When I was running to save my life, I fell in the river and was shot. I climbed out of the river and into the graveyard. And there was my sister ... I saw one of my sisters shot in the face. She had blood all over her face. I fainted. When I woke up a man was carrying me. He was running. I woke up and along the way I saw my young brother.” Johura spent 14 days in hospital. She now lives with her brother and her aunt in one of the sprawling refugee camps for Rohingya in Bangladesh. She talks about life now, one year since she fled: “A lot of kids can call for their parents but we don’t have parents to call out to. Whenever I can’t call for my parents, I don’t feel peaceful. Whenever I feel the pain (from the wound), or think about what the military people did in Myanmar, I remember that. I don’t feel good at all here, I want to see my parents and siblings. I have to live in someone else’s house, I don’t like it ... The other kids are peaceful, that’s why they are playing. I’m not peaceful in my body and that’s why I can’t play. My brother and I have all the worries of this world."

60-year-old Suru Jaman came to Bangladesh two days before the Muslim festival of Eid. “I didn’t understand what was happening. My neighbors pushed me onto the boat to save me. We could not even bring one piece of clothing. We didn’t have much space to bury people so we had to put nine or 10 people in one grave.” She now lives in the megacamp with her 19 year old daughter. “My husband is dead ... he was killed by those people. Whenever I remember the things that happened, I feel like killing myself, stabbing myself in the chest.” At least they are safe now, she says: “We were not peaceful back there. We are peaceful now. We can eat and pray.”

47-year-old Rohingya refugee Abdul Hafez fled the attacks by the Myanmar military five days after Eid, in September 2017. “When I was in my country I used to be a farmer, that’s how I used to provide for my family. Now in Bangladesh I can’t find work. I’m going through a very hard time because I can’t provide the things that my women and children are looking for.” His family survived the violence, but it has left everyone troubled: “I often remember what happened. I try not to be angry, sad, frustrated. I try to bury that pain and sleep more. Some days in my dreams I see what happened there, like them hitting people. I see these things often.”

20-year-old Rohingya refugee Salima Khatun came to Bangladesh from Myanmar in September 2017. “The military came at 3am,” says Salima. She explains how they took the women aside and handcuffed the men. Then, in front of the men, they started raping the women from the village. “My husband tried to save me,” she says. Her six-year-old son was standing with her husband when he rose to his feet and tried to stop the military men from raping his wife. One of the military men raised his gun and shot at her husband. He missed. The bullet killed her son instead. The military men then went to beat her husband “with their hands, their rifles, their boots.” Then they loaded the men into vehicles and drove them away. “That was the last time I saw my husband,” she says. One year later, from the sprawling refugee camp that’s now her home, she speaks of the pain she still feels: “When I remember the torture by the military I feel very painful in my heart. Every night I remember what happened. All the time I’m happy in the camp but at night, when I’m alone, I feel bad.”

Rohima Khatun, a 25-year-old Rohingya refugee, fled her Rakhine village and arrived in Bangladesh in September 2017. “We came to Bangladesh because the Mogh (derogatory term for local Rakhine Buddhists) were torturing us. They told us that we had no right to stay in Myanmar, and we should go back to Bangladesh.” She explains what happened to her: “First the military called a meeting. Those people who stay in their houses will be okay, they said, but those who move from place to place will be arrested. At 4am the next morning they came back and surrounded the village. They separated the men and women. They handcuffed the men and started raping the young girls. The men were shouting and so were the children. They started beating them.” They set fire to the houses. Military men went to rape her she said, but when they saw she was seven months pregnant and carrying a four-year old child they left her. The child was terrified and started screaming: “The four-year-old was crying so they took the child from me and threw him in the fire. They also shot my husband in front of me in the yard of our house.” She discusses life now, a year later: “Every single moment I remember this and get emotional because I lost my neighbors, husband, child, relatives.”

Since August 2017, MSF has conducted over 16,000 individual mental health consultations and 18,000 group mental health sessions among Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district. All MSF health facilities provide mental health services, and both psychological and psychiatric services are available at all inpatient facilities and some primary health centres.

MSF is one of very few actors providing such services to both Rohingya and Bangladeshi patients in Cox’s Bazar district. The limited availability of mental health services and particularly more advanced mental health services, including psychiatric care, in the area, remains concerning.

Find out more about the Rohingya refugee crisis here.