Barriers to accessing diabetes care include a lack of resources and training to provide a minimum standard of care, insufficient monitoring systems, and limited capacity to improve insulin regimens.

People living with insulin-dependent diabetes rely on insulin replacement and blood sugar self-monitoring, yet these are often unavailable or inaccessible in low-resource settings. In these settings, insulin is usually administered in vials with syringes instead of insulin pens, which are more common in high-income countries and are preferred by patients because they are easier to use, less painful, and less associated with stigma.

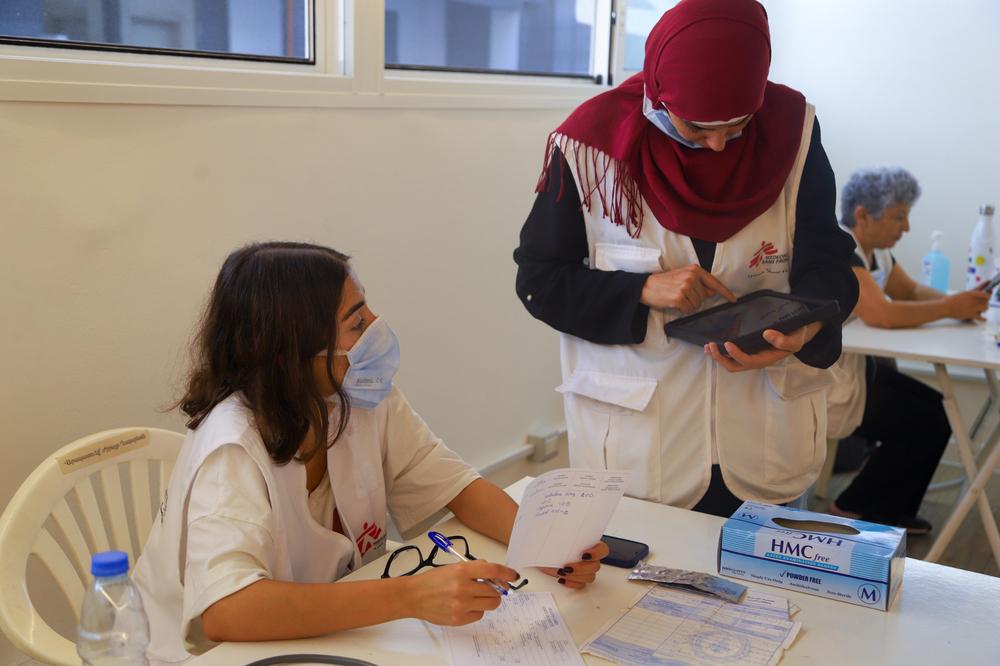

Instead, most patients in the places MSF works are expected to go to outpatient facilities twice a day for insulin injections. People often have to travel significant distances to access the closest facility, sometimes by foot, so this disruption has an impact on their ability to go to school or work.

This is also the absolute minimum number of times per day required to manage type 1 diabetes, though in high income countries the standard is to follow a highly tailored regimen of insulin throughout the day corresponding to their diet and physical activity. In order to provide these kinds of insulin regimens, people need to be able to self-inject insulin at home, and both patients and clinicians need to know the patients’ blood sugar levels throughout the day as they go about their usual activities. Because self-monitoring of blood sugar is almost completely inaccessible in low- and middle-income countries, largely due to cost, there is no such visibility, which makes it difficult to find a safe, effective insulin dose.

Type 2 diabetes treatment usually starts with oral medication since the person is still producing insulin but they are becoming less sensitive to it. Without early management of the disease, it can progress to the insulin-dependent form. The first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes is a medication called Metformin, which is somewhat accessible in low- and middle-income countries, but there are many more options in high-income countries, where treatment has greatly expanded in recent years to include new classes of medications that help control blood sugar levels and actively protect organs like the kidneys. These medications serve a vital role is controlling blood sugar, preventing complications, and preventing the need to start insulin.

Patients with type 2 diabetes are often highly resistant to starting insulin because of shame, stigma, and the practical or logistical challenges associated with it. However, these crucial medications are almost completely inaccessible in places where MSF works due to the cost, resulting in more patients with complications and more patients navigating the transition to insulin.